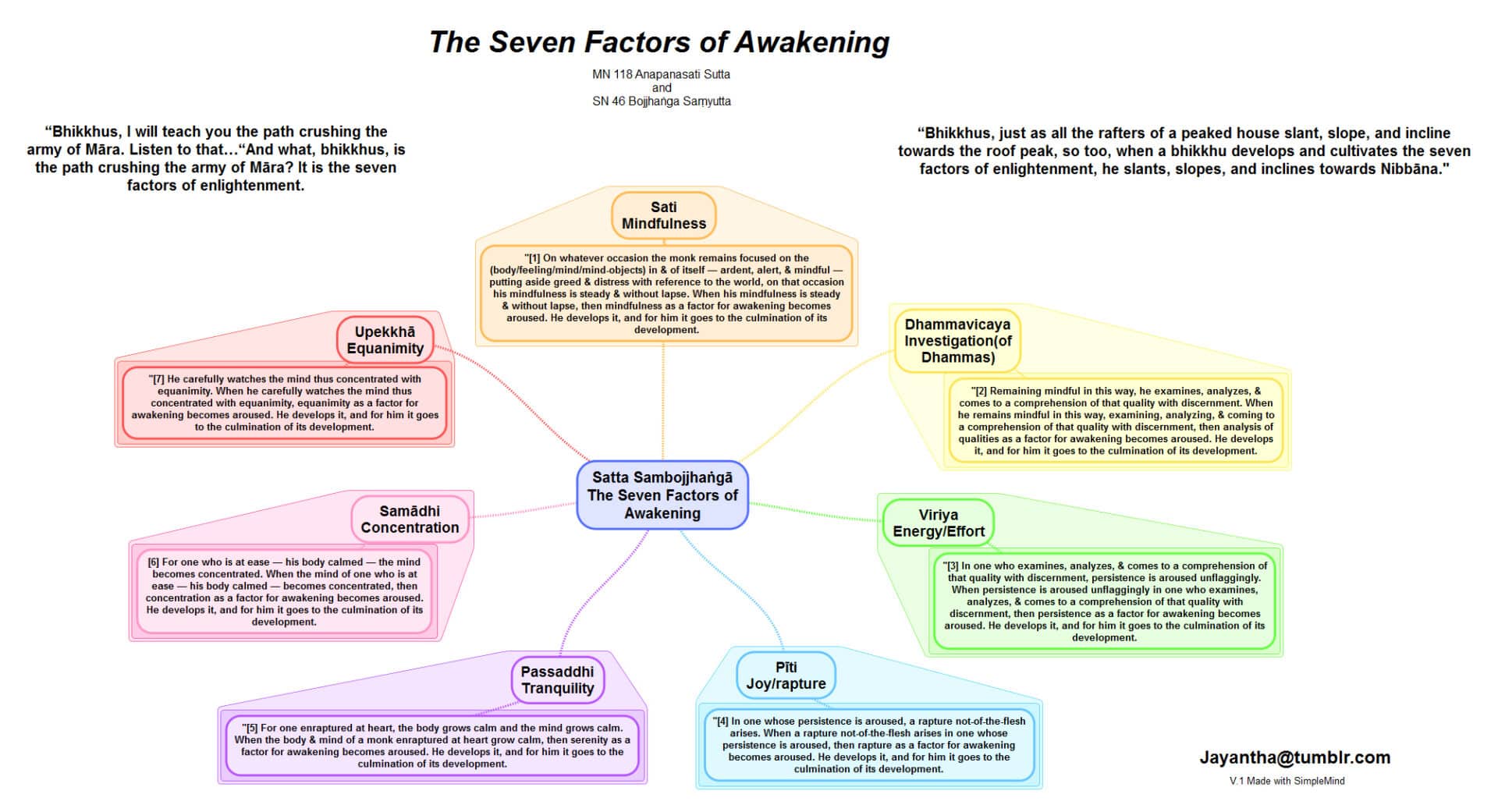

The seven factors of awakening are:

1) mindfulness

2) investigation

3) energy

4) rapture

5) tranquility

6) concentration

7) equanimity

We have three concepts from the five spiritual faculties

(mindfulness, energy, and concentration)

and four that seem new but have already been touched on to some degree.

The order here is closely related to the stages of insight,

which is a map of the standard stages

through which diligent insight meditators cycle.

MINDFULNESS

Mindfulness can be very useful in sorting out

which sensations are mental, and which are physical.

We need to know the elemental sensations that make up our world.

This is the crucial foundation of insight practices.

Not surprisingly,

the first classic insight that leads to all the others is called

“knowledge of mind and bodyâ€

and arises when we learn to clearly distinguish between the two as they occur.

We can know where sensations are in relation to each other.

We can know exactly when they occur

and how they change during their very brief stay.

We can and should sort these out as best we can.

Be patient and precise.

Become fluent in all the sensations and patterns that make up your reality.

Increasing our direct sensate clarity through repeated attention to doing so

is the point of mindfulness in this context.

We are wiring the machine of our brain to be able to

be more present to exactly what is going on in our experience.

These two paragraphs contain formal insight practice instructions,

so perhaps go back and read them a few times.

Noting is the exercise that gained for me the most breaks and insights

in my early practice, particularly when done on retreats,

and because of that my enthusiasm for it is extreme.

I still consider it the core foundation of my early to middle practice,

the technique that I fell back on when things turned difficult

or

when I really wanted to push deep into new insight territory.

Thus,

of all the techniques and emphases I mention in this book,

take this one the most seriously

and give it the most attention.

Its simplicity belies its astonishing power.

~~~

The practice is this:

Make a quiet, mental one-word note

of whatever you experience in each moment.

Try to stay with the sensations of breathing,

which may occur in many places, noting these quickly as “risingâ€

(as many times as the sensations of the breath rising are experienced)

and then “falling†in the same way.

These are the fundamental insight practice instructions.

When the mind wanders, notes might include

“thinkingâ€, “feelingâ€, “pressureâ€, “tensionâ€, “wanderingâ€, “anticipatingâ€, “seeingâ€, “hearingâ€, “coldâ€, “hotâ€, “painâ€, “pleasureâ€, etc.

Note these sensations one by one as they occur

and then return to the sensations of breathing.

When walking, note the feet moving as “lifting†and “placingâ€,

or as “liftingâ€, “movingâ€, and “placingâ€

as you perceive each of the many sensations of all those processes,

noticing other sensations as they arise and

returning simply to the sensations of the feet walking.

~~~

INVESTIGATION

Once we start to know what our objects are, what our actual reality is,

we can get down to the good stuff:

knowing the truth of these things called, appropriately,

“Investigation of the truth†or “investigation of the dharma†(Pali dhamma).

Dharma here just means “truthâ€,

and it is sometimes used to mean the specific truths the Buddha taught.

The word can also mean moments of experience,

the actual, flickering sensate basis of our world,

and it is these dhammas that we investigate.

So,

once mindfulness has made these dhammas, these moments of experience,

a bit clearer, we can know that

things come and go, don’t satisfy, and ain’t us.

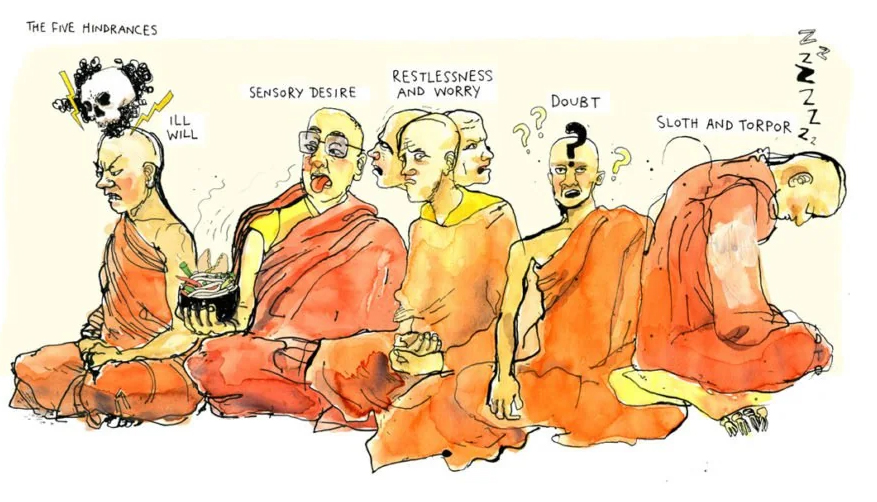

The hindrances:

Are an extremely important topic,

but they can easily begin to seem more ominous than they really are.

The hindrances are formally listed as:

Sensory desire

Ill will or malice

Sloth/torpor

Restlessness/worry

Doubt

Each of these states of mind will inhibit meditative progress

if we are not aware of them

as sensate objects for investigation as they arise.

Hindrances are anything of which we were not mindful

and of which we did not investigate the truth.

Now that we know to be mindful and investigate

the three characteristics of all moment-to-moment experiences,

there will only be hindrances when we forget to do this.

If we do not forget, there will be no hindrances.

No phenomenon is inherently a hindrance

unless we do not understand the sensations that make it up.

When we know deeply that all of these are of the nature of ultimate truth,

phenomena cease to be a fundamental problem.

Specifically,

noticing the many little rapid sensations that make up

sensory desire, ill will, sloth, torpor, restlessness, worry, and doubt

is insight practice.

Sometimes noticing what those really are

is more profound and useful than noticing aspects of our intended primary object.

~~~

There is an important shift that happens

when we go from caring so much about what is going on,

such as judgment, boredom, restlessness, or whatever,

and switch to

caring about whether we knew the sensations of what was going on.

A meditator who doesn’t get this

might get all stressed about their mind wandering.

A more seasoned insight meditator is excited when they can

Note – “wandering†and perceive the wandering as sensations.

See the difference?

The same goes for all the other “hindrancesâ€,

since,

if you note them, they aren’t hindrances.

“Doubtâ€, “fearâ€, “irritationâ€, “dullnessâ€, and the like

are all great notes to make whenever those arise.

You can note them again and again if they tend to linger,

and that noting of those qualities is solid insight practice.

Yay, noting!

In this way,

we gradually transform the hindrances from

an impediment to practice

into a reason to practice,

then we transform them into an integral part of the practice itself,

and finally we find them as much a basis of wisdom as anything else.

ENERGY – the third of the seven factors.

We diligently investigate the ultimate truth of our experience,

and this can be invigorating once we get into it.

Energy is a good thing,

as it obviously fuels and invigorates our practice.

Tranquility, is the natural counterbalance to energy,

and in that and subsequent sections I will talk about

how to try to balance our practice,

realizing that this balance will be a moving target.

If you are on the runway to Crazyland from

jacking the energy too high for too long,

figure out how to

gently settle into the things that are arising naturally on their own

rather than pouring energy into practice.

Reality is constantly showing up in amazing detail,

and if your mind is receptive,

all that detail will reveal itself without you having to do much of anything,

and that is the best kind of energy—

energy that doesn’t really feel like energy

but gets the job done.

~~~

One of the keys to mobilizing energy is motivation,

so if energy is lacking,

try to remember why you are doing all of this.

RAPTURE

When energy comes online with mindfulness and investigation,

this can produce something called “raptureâ€,

which has two general meanings,

the first of which relates to deep joy, pleasure, and enthusiasm.

These are valuable spiritual qualities.

Be open to the joy and happiness life can bring.

Natural wonder really helps many things,

including and specifically investigation.

~~~

Reality is simply amazing. Our minds are amazing.

The vast intricacy of what happens in each moment is truly remarkable.

When you sit, sit with amazement at what is going on,

like a vast, complex, rich work of moving, fluxing art.

When you walk,

walk with a sense of wonder at all the little aspects of

movement, of balancing, of a body moving through the air,

through a changing landscape,

with all the little facets that make that up.

The feel of our foot touching the floor, earth, sand, grass, moss, leaves, stones,

or whatever we are walking on is simply amazing.

Air is amazing. Breathing is amazing.

That we think is amazing.

Food is amazing.

Have you really looked at a glass of water lately?

When tasting, smelling, hearing, seeing,

feeling, thinking, speaking, eating,

and doing anything else,

really tune in to how fascinating it is to perceive all these things.

This natural curiosity,

this enchantment with the experience of the ordinary world,

is total gold.

~~~

Spiritual practice can also produce all kinds of odd experiences,

some of which can be very intense, bizarre, and far out.

This is the second common connotation of the word “raptureâ€,

and these experiences are commonly referred to in this and other traditions as

“rapturesâ€.

So,

when the word is in the singular, “raptureâ€,

this means being enraptured with your sensate world.

It can also mean an upwelling of pleasant euphoria,

as we will see in the section that maps concentration states.

However,

when I use the word in the plural, “rapturesâ€,

this means strange meditation side effects.

Some of these experiences that I will refer to generically as raptures

might be pleasant, some may be weird,

and some might completely suck.

The take-home here is that

rapture and raptures are to be understood as they are

and should be related to wisely, accepting all sensations that make them up,

be they pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral.

Learn when to put the brakes on practice

if the difficult raptures are teaching you their important lessons

a bit too fast for you to keep it together,

and learn how to open to the wonderful joy and bliss

that spiritual practice may sometimes produce.

TRANQUILITY

Joy, bliss, and rapture are relatively satisfying things,

and this satisfaction can produce tranquility.

We can associate being peaceful with tranquility.

Focusing on tranquility and a more spacious and silent perspective

in the face of difficult raptures can help you ride them out,

and just sitting silently and observing reality do its thing

can be very powerful practice.

Tranquility is a good thing in meditation.

A mind that is not tranquil

will have a harder time concentrating and being balanced.

Simple as that.

Being kind and moral also help develop tranquility, as moral conduct

lessens harsh and therefore agitating thought and behavior patterns,

which necessarily obstruct tranquility.

Real tranquility often comes naturally,

though it may be skillfully cultivated as well,

such as by just tuning in to that quality as an exercise in calm abiding,

or more formally

by doing concentration practices and

cultivating deep states of stillness and peace,

the afterglow of which can be very useful for investigation

if we can rouse up a little energy and interest afterwards.

Cultivating equanimity is helpful for developing tranquility,

as is deepening in pure concentration practices, the second spiritual training.

Tranquility, concentration, and equanimity are intimately related.

CONCENTRATION

One of the challenges of deep tranquility is keeping the mind concentrated.

This may seem like a direct contradiction to what I have just said,

but there may be stages of practice where there can be so much tranquility

that the mind can become dull and hard to focus.

So,

just as tranquility is good for concentration and acceptance,

too much is similar to not having enough energy.

Remember,

balance and strengthen, strengthen and balance.

As these are the seven factors of awakening,

they apply directly to insight practices and training in wisdom.

Thus,

the concentration referred to here is a very different kind of concentration

than that used for attaining high concentration states.

It is called “momentary concentrationâ€.

In the context of insight, concentration really means

that we can consistently investigate each sensation that arises,

one after the other, second after second, minute after minute, hour after hour.

When we can practice moment after moment, sensation after sensation,

but just before we shift into the stages of insight

this is also ‘access’ concentration,

only achieved with a different set of emphases,

and it will shortly lead to the stages of insight.

In this way, we have stability in our ability to investigate,

in that it can happen again and again without interruption,

but

we are not trying to attain stable states or anything else,

since we are doing insight practices.

EQUANIMITY

Concentration can produce great stability and consistency of mind,

and this can lead to equanimity,

which is that quality of mind that is okay with things;

or balanced in the face of any internal or external painful, pleasurable,

or neutral condition, including a lack of equanimity.

This may sound a bit strange, but it is well worth considering.

Equanimity also relates to

a lack of struggle even when struggling,

to effortlessness even in effort,

to peacefulness even when there is no tranquility.

When equanimity is well developed,

we are not frightened of being afraid,

not concerned by being worried,

not irritated by being annoyed,

not pissed off by being angry, etc.

Phenomena do not disturb space or even fundamentally disturb themselves

from a certain point of view.

I have wept and yet been very equanimous about it,

if that helps clarify what I am talking about.

~~~

Equanimity can be regarded as a meta-perspective able to hold everything else.

There are lots of different technical uses of the term equanimity in Buddhism,

so watch for its various meanings in different contexts.

Real equanimity has a spaciousness to it, an openness,

a flowing, volumetric component that is important.

Once again, we are back to knowing this moment just as it is.

This “just as it is†quality is related to mindfulness and to equanimity.

In the end,

we must accept the truth of our specific lives, of our minds, of our neuroses,

of our “defilementsâ€, of impermanence, of suffering, and of emptiness.

We must accept this,

and this is what they are talking about when they say just

“open to itâ€,

“be with itâ€,

“let it beâ€,

“let it goâ€, and so on.

From a pure insight practice point of view,

you can’t ever fundamentally “let go†of anything,

so

I sometimes wish the popularity of this misleading and

apathy-producing admonition would decline,

or at least be properly explained or challenged.

However,

if you simply investigate the truth of the three characteristics of the sensations that seem to be solid,

you will come to the wondrous realization that

reality is continually “letting go†of itself.

Thus,

“Let it go†means,

“Don’t artificially solidify a bunch of transient sensations.â€

It does not mean,

“Stop feeling or caring,â€

nor does it mean,

“Pretend that the noise in your mind is not there.â€

If people start with “just open to it†yet

don’t develop both strong mindfulness and careful investigation into the three characteristics

to gain deep insights,

their practice may be less like meditation and more like psychotherapy,

day dreaming, cultivated passivity, denial, or even

self-absorbed, spiritually-rationalized, neurotic indulgence in mind noise.

Noticing again and again the prevalence of this activity and

the pervasive and absurd notion that

there is no point in trying to get awakened

has largely demolished my vision of being

a happy meditation teacher in some mainstream meditation center.

On the other hand,

even if you gain all kinds of strong concentration,

look deeply into impermanence, suffering, and no-self,

but can’t open to these things, can’t let them be,

can’t accept the seemingly absurd and frightening truths of your experience,

then

you will likely be stuck in hell until you can,

particularly in some of the higher stages of insight practices.

Plenty of people practice based on a model that idealizes

objectifying all feelings and sensations.

Because of this ideal,

they hold their emotions at arm’s length and cultivate

immunity or passivity to them.

The ideal of

“letting it all come and go without attaching any importance to any of itâ€

sounds so very nice, so very “Buddhistâ€.

However,

instead of cultivating actual equanimity,

they accidentally cultivate

denial, repression, dissociation, depersonalization, derealization,

and a stabilized illusion of some split-off and distant or “objective†observer.

This indifference and denial can easily flip over into ugly and treacherous forms of

passive aggression.

Beware of this trap,

as it is extremely common and is the exact opposite of insight practices,

being largely a dressed-up exercise in finely honed

aversion and ignorance

rather than a careful investigation of this real human life.

To balance and perfect the seven factors of awakening

is sufficient cause for awakening.

Thus,

checking in from time to time with this list and seeing how you are doing

and what might need improvement is a good idea.

Just having this list in the back of your mind can be helpful.

Finally,

we learn that we cannot get rid of all the bumps on our road,

so having the shock absorbers of equanimity,

the ability to remain spacious, even-minded, and accepting of what life brings,

including our honest, human, and understandable reactions,

is also very helpful for crafting a good and healthy life.

The scope of the first training, morality,

is the ordinary world, the conventional world,

the world that we are all familiar with

before we even consider more specialized topics such as meditation.

The goal is to think, speak, and act in ways that are conducive to

the reduction of suffering as well as the welfare of ourselves and others.

~~~

The scope of the second training, concentration,

is to focus on very specific and limited objects of meditation and thus

attain specific altered states of consciousness that

cultivate positive mental qualities and reduce negative ones.

~~~

The scope of the third training, that of insight or wisdom,

is to shift to perceiving reality at the level of individual sensations,

perceive their three characteristics, and thus

attain profound insights into the nature of reality

and realize stages of awakening.

This article was Inspired by

Buddha’s step by step instructions to obtain Enlightenment

as refined by The Arahant Daneil M. Ingram.