This is a set of stages that diligent meditators pass through on the path of insight.

Some of the “content-based†or psychological insights into ourselves

can be interesting and helpful, but when I say “insightâ€,

these stages with their specific perceptual shifts and upgrades

are what I am talking about.

These are formally known as “Knowledge of†or “Insight intoâ€

They are also called ñanas, which means “knowledgesâ€,

These are stages of heightened perception into the truth of all phenomena,

opportunities to see directly how sensate reality is,

but they are not seemingly stable states

like those cultivated in concentration practice.

~~~

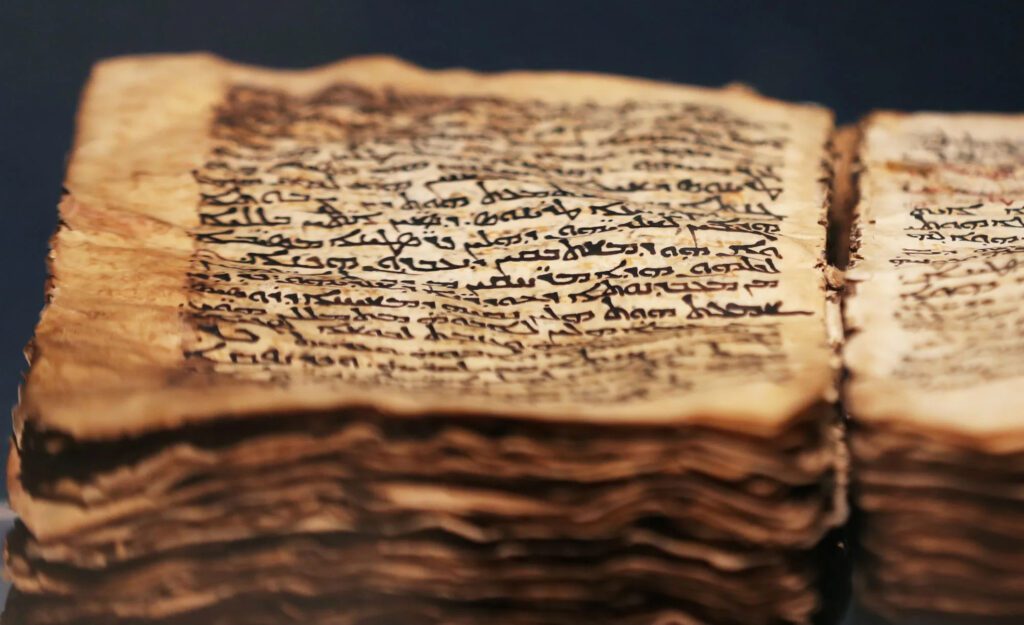

One of the most profound things about these insight stages is

that they are strangely predictable regardless of the practitioner

or the insight tradition.

Texts that are 2,000 years old describe the stages

just the way people go through them today,

though there will be some individual variation with respect to

the individual specifics today as then.

The Christian maps, the Sufi maps, the Buddhist maps of the Tibetans and the Theravada, the maps of the Kabbalists, and many non-Buddhist traditions of India are all remarkably consistent in their fundamentals.

I chanced upon these classic experiences before I had any training in meditation, and I have met many people who have done likewise.

These maps, Buddhist or otherwise, are talking about something inherent to

how our minds progress in fundamental wisdom

that has little to do with any tradition

and much to do with the mysteries of the human mind and body.

The maps are describing basic human development.

These stages are not Buddhist, but universal,

and Buddhism is merely one of the traditions that describes them,

albeit unusually well.

St. John of the Cross’ Dark Night of the Soul

does a good job of dealing with the most difficult of the insight stages.

His map is often called “The Ladder of Loveâ€.

~~~

If the meditator really is into insight territory, then continued,

correct, sensation-based practice has a way of facilitating progress given time.

Also,

when the proverbial crap is hitting the fan,

having a map can help the meditator not make too many of the

common, tempting, and occasionally disastrous blunders of that stage,

as well as provide the meditator with encouragement that they are

on the right track when they hit the grueling, weird, or captivating stages.

Contextualization and knowing that some of the strange or hard stuff is

expected, normal, and doesn’t last can be extremely important

to help people find the courage and perspective needed to persevere.

These stages can significantly color or skew a meditator’s view of their

life and experience until they master them,

and it can be alleviating and even life-saving to remember this

when navigating rougher waters while trying to remain functional

in our endeavors and relationships.

~~~

Those who do not have the benefit of the maps in these situations

or who choose to ignore them are much more easily blindsided

by the psychological extremes and challenges that may sometimes

accompany stages such as the Arising and Passing Away and

those of the Dark Night.

At the very least,

the maps clearly demonstrate that there is vastly more to all this

than just philosophy or psychology.

They also clearly and unambiguously point to how the game is played

step-by-step and stage-by-stage,

what we are looking for, and, more importantly, why;

and they provide guidelines for how to avoid screwing up along the way.

~~~

The maps fill in the juicy details of the seemingly vast gap from

doing some seemingly boring and simple practice… to getting awakened.

The more intense, consistent, and precise the practice,

the easier it is to see how the maps apply.

The more energy and focus are dedicated to practice,

the more dramatic and even outrageous these stages can be.

~~~

If these stages unfold gently over long periods of time,

it can be more difficult to discern the progression through them,

though it does happen.

Certain emphases in practice, such as Mahasi Sayadaw–style noting practice,

particularly on intensive retreats,

seem to produce a clearer appreciation of the maps,

and some individuals will have an easier time than others

seeing how these maps apply.

Each stage is marked by very specific increases in our perceptual abilities.

The basic areas we can improve in are:

clarity, precision, speed, consistency, inclusiveness, and acceptance.

These improvements in our perceptual abilities are the hallmarks of each stage

and the gold standard by which they are defined and known.

Each stage also tends to bring up mental and physical raptures

(unusual manifestations).

These are predictable at each stage and sometimes very unique to each stage.

They are secondary to the increase in perceptual thresholds

by which we may judge whether we are at a specific stage.

Each stage also tends to bring up specific aspects of our

emotional and psychological makeup.

These are also strangely predictable,

but not as reliable for determining which stage is occurring.

The emotions that might show up are suggestible, scriptable, ordinary,

and will show more variation from person to person.

However,

when used in conjunction with the changes in perceptual threshold

and the raptures,

they can help us gain a clearer sense of which stage has been attained.

Further,

these stages occur in a very predictable order,

and so looking for a pattern of stages leading us to the next

can help us get a sense of what is going on.

Thus,

when reading my descriptions of these stages,

pay attention to these distinct aspects:

1) the shift in perceptual threshold;

2) the physical and mental raptures;

3) the emotional and psychological tendencies; and

4) the overall pattern of how that stage fits with the rest.

So, we sit down (or lie down, stand, walk)

and begin to perceive every sensation clearly as it is.

When we gain enough concentration

to steady the mind on the object of meditation,

something called “access concentrationâ€,

we may enter the first jhana, now called the “first vipassana jhanaâ€,

which is in some ways the same initially for both

concentration practice and insight practice.

However,

as we have been practicing insight meditation,

we are not trying to solidify this state,

but rather trying to penetrate the three illusions of

permanence, satisfactoriness, and self

by understanding the three characteristics.

We try to sort out with mindfulness what are physical sensations

and what are mental sensations,

and when these are and are not present in our direct experience.

We try to be clear about the actual sensations, just as they are,

that make up our world.

We try to directly understand the three characteristics moment to moment

in whatever sensations arise, be it in a restricted area of space,

such as the areas in which the sensations of breathing arise;

or a moving area, as in the case of body-scanning practices;

or in the whole of our world,

as is done in what are generally called “choiceless awareness†practices,

using some other technique or object, such as noting,

or

just by being alive and paying attention.

Thus,

the first stage has a different quality to it from that of concentration practice,

and we attain direct and clear perception of the first knowledge of

Mind and Body.

This article was Inspired by

Buddha’s step by step instructions to obtain Enlightenment

as refined by The Arahant Daneil M. Ingram.